The Hidden Math of Text: A Guide to Quantitative Analysis

1. Introduction

Every piece of text tells two stories. The first is semantic—the meaning conveyed through words and sentences. The second is statistical—the underlying patterns in character distributions, structural regularities, and information density. While natural language processing (NLP) has made remarkable strides in understanding the semantic story, the statistical story remains equally powerful and, in many contexts, more computationally efficient.

This post explores quantitative techniques for analyzing textual data without relying on large language models or semantic understanding.

We'll draw from an implementation of 70+ metrics designed for comprehensive text analysis, covering everything from classical Shannon entropy to pattern-based structural flags.

2. Motivation: Why Measure Text Quantitatively?

The Semantic Gap Problem

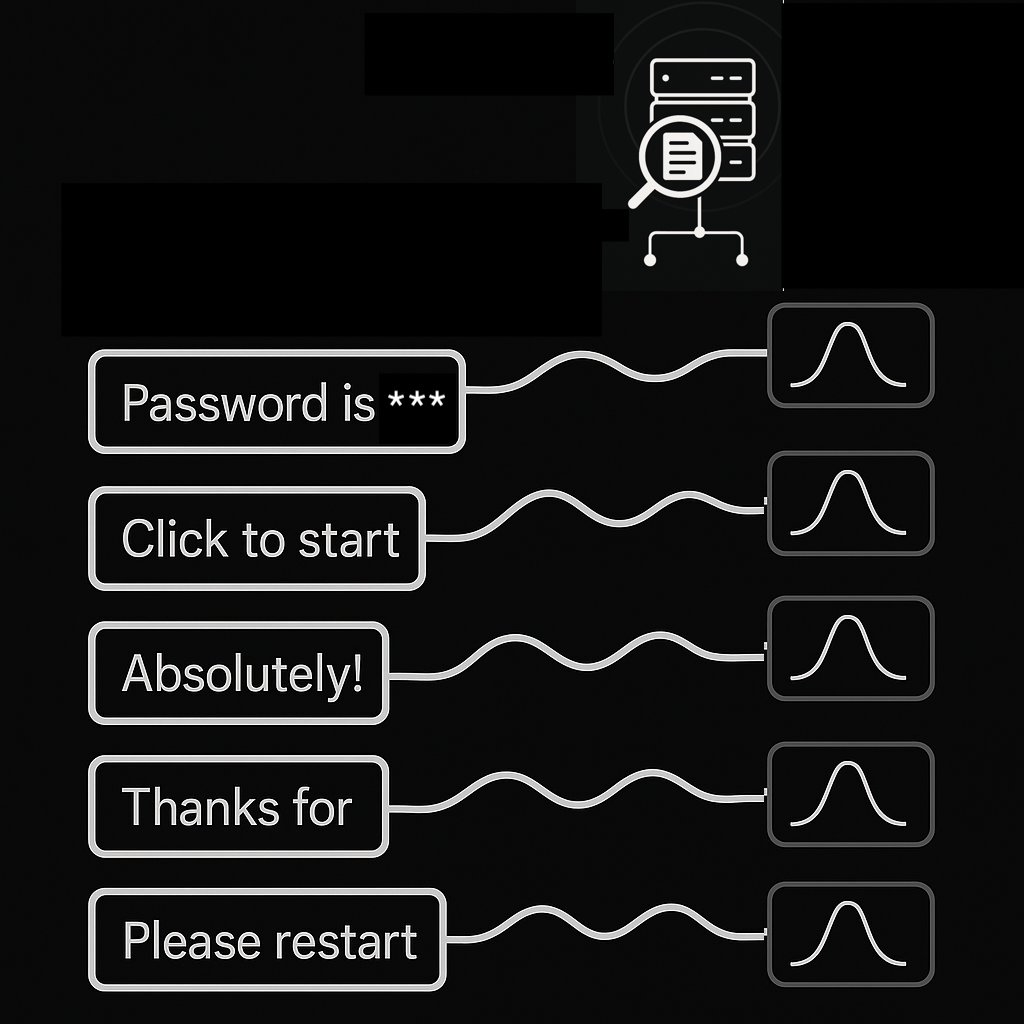

Traditional NLP approaches require understanding context, grammar, and meaning. But many practical problems don't need semantic understanding—they need pattern recognition at the character and structural level.

Consider these strings:

sk_live_4eC39HqLyjWDarjtT1zdp7dc

Hello, how are you doing today?

aGVsbG8gd29ybGQ=

2024-01-15T10:30:00ZA human immediately recognizes these as: an API key, conversational text, Base64-encoded data, and an ISO timestamp. But the recognition isn't semantic—it's pattern-based. We notice:

- The API key's prefix pattern and random character distribution

- The natural language's word boundaries and predictable letter frequencies

- Base64's restricted character set

- The timestamp's rigid structure

Quantitative metrics can capture these same distinctions programmatically, often in microseconds, without loading multi-gigabyte models.

Use Cases That Demand Quantitative Analysis

| Domain | Application | Why Quantitative? |

| Security | Credential detection in logs | Secrets have measurably high entropy |

| Data Quality | Synthetic data validation | Match distribution characteristics, not meaning |

| Compliance | PII detection | Structural patterns (emails, SSNs) have signatures |

| DevOps | Log classification | Code vs. stack traces vs. user input differ structurally |

| Research | Corpus analysis | Compare text collections at scale |

3. Foundations: Information Theory and Data Distribution

Before diving into specific metrics, we need to understand the theoretical foundation: information theory, pioneered by Claude Shannon in 1948.

The Core Insight: Surprisal

Information theory is built on a simple premise: Information is the resolution of uncertainty.

Imagine you are playing Wheel of Fortune.

- If the puzzle reveals the letter Q, you intuitively expect the next letter to be u. If it is u, you aren't surprised. That u carried very little information because it was predictable.

- If the letter following Q is z, you are shocked. That z carries high information because it was highly improbable.

This is Surprisal. The less probable a character is, the more "information" it carries.

Surprisal (or self-information) of a character x:

Where P(x) is the probability of character x appearing. Lower probability = higher surprisal = more information bits.

Character Probability Distribution

For any text sample, we can compute a probability distribution over characters:

from collections import Counter

def char_distribution(text: str) -> dict[str, float]:

counts = Counter(text)

total = len(text)

return {char: count / total for char, count in counts.items()}This distribution is the foundation for all entropy calculations.

Alphabet Size: The Diversity Measure

The alphabet size (number of unique characters) immediately tells us about text diversity:

| Text Type | Typical Alphabet Size |

| Binary data | 2 (0, 1) |

| Hex strings | 16-22 (0-9, a-f, maybe A-F) |

| Lowercase English | 26-30 |

| Mixed case + numbers | 50-70 |

| Full Unicode text | 100+ |

| Random bytes | 200+ |

4. Entropy Metrics: The Core Toolkit

4.1 Shannon Entropy (Bits Per Character)

The foundational metric. Shannon entropy measures the average information content per character.

Formula:

Interpretation:

- Units: Bits per character (bpc)

- Range: 0 to log₂(alphabet_size)

- Low entropy: Predictable, repetitive text

- High entropy: Uniform distribution, high randomness

Implementation:

import math

from collections import Counter

def shannon_bpc(text: str) -> float:

if len(text) <= 1:

return 0.0

counts = Counter(text)

total = len(text)

entropy = 0.0

for count in counts.values():

p = count / total

entropy -= p * math.log2(p)

return entropyKey insight: Shannon entropy captures the theoretical minimum bits needed to encode each character, given the observed distribution.

4.2 Miller-Madow Bias-Corrected Entropy

Shannon entropy is biased for small samples—it tends to underestimate true entropy. Miller and Madow (1955) proposed a correction:

Formula:

Where:

- K = number of distinct characters (alphabet size)

- N = string length

When to use: When analyzing short strings (< 100 characters) where Shannon's bias is significant.

Implementation:

def miller_madow_bpc(text: str) -> float:

if len(text) <= 1:

return 0.0

shannon = shannon_bpc(text)

k = len(set(text)) # distinct characters

n = len(text)

correction = (k - 1) / (2 * n)

return shannon + correction4.3 Normalized Entropy

Different texts have different maximum possible entropies (based on alphabet size). To compare apples to apples, normalize:

Formula:

Interpretation:

- Range: [0, 1]

- 1.0: Maximum entropy (perfectly uniform distribution)

- 0.0: Minimum entropy (single character repeated)

Why it matters: A hex string with entropy 3.8 bpc and natural language with entropy 4.2 bpc aren't directly comparable. But normalized entropy reveals that the hex string (3.8/4.0 = 0.95) is relatively more random within its alphabet than the natural language text (4.2/6.5 ≈ 0.65).

4.4 Min-Entropy (Rényi Entropy of Order ∞)

For security analysis, average entropy isn't enough. Min-entropy gives the worst-case guarantee based on the most probable character:

Formula:

Interpretation:

- Always ≤ Shannon entropy

- Security applications should use min-entropy, not Shannon entropy

- Represents the minimum bits of unpredictability

Example:

String: "aaaaabbbcc"

Most frequent: 'a' appears 5/10 = 50%

Min-entropy: -log₂(0.5) = 1.0 bit

Shannon entropy: ~1.49 bits (higher, but misleading for security)

4.5 Compression-Based Entropy (Gzip BPC)

Theoretical entropy metrics assume independent characters. Real text has structure: words, grammar, patterns. Compression-based entropy captures this (similar to Kolmogorov complexity):

Formula:

Why gzip?

- Captures character-level entropy (like Shannon)

- Also captures sequential patterns (n-grams)

- Reflects practical compressibility

Implementation:

import gzip

def gzip_bpc(text: str) -> float:

if not text:

return 0.0

text_bytes = text.encode('utf-8')

compressed = gzip.compress(text_bytes, compresslevel=9)

return (len(compressed) * 8) / len(text)Typical values:

Text TypeGzip BPCHighly repetitive0.1 - 1.0Natural language2.0 - 4.0Random alphanumeric6.0 - 8.0Random bytes8.0+

4.6 Compression Ratio

The inverse perspective on compressibility:

Formula:

Higher ratio = more compressible = more redundancy/patterns.

4.7 Cross-Entropy (Language Model Based)

Cross-entropy measures how well a trained model predicts the text:

Formula:

Interpretation:

- Low cross-entropy: Text matches the model's training distribution

- High cross-entropy: Text is out-of-distribution (OOD)

Use case: Train an n-gram model on "normal" text, then use cross-entropy to detect anomalies.

Perplexity is simply:

4.8 N-gram Entropy (Bigram and Trigram)

Character-level entropy ignores sequential dependencies. N-gram entropy captures local patterns:

Bigram entropy: Entropy over 2-character sequences Trigram entropy: Entropy over 3-character sequences

Why it matters:

- "th" is common in English (low bigram surprisal)

- "qx" is rare (high bigram surprisal)

- Natural language has low n-gram entropy relative to random text

5. Beyond Entropy: Complementary Metrics

Entropy metrics are powerful but not sufficient. A comprehensive analysis toolkit includes:

5.1 Character Composition Analysis

Character class counts and ratios:

| Metric | Description | Use Case |

| char_lower / ratio_lower | Lowercase letters | Language vs. code detection |

| char_upper / ratio_upper | Uppercase letters | Acronyms, constants, emphasis |

| char_digit / ratio_digit | Digits | IDs, numbers, hex detection |

| char_special / ratio_special | Punctuation/symbols | Code, URLs, formatting |

| char_whitespace | Spaces, tabs, newlines | Prose vs. dense data |

| ratio_alpha | (lower + upper) / length | Text vs. numeric content |

| ratio_alphanum | (alpha + digit) / length | Readable content ratio |

5.2 Pattern Detection

Case patterns:

class CasePattern(Enum):

UPPER # "HELLO WORLD"

LOWER # "hello world"

MIXED # "HeLLo WoRLd"

TITLE # "Hello World"

CAMEL # "helloWorld"

SNAKE # "hello_world"

KEBAB # "hello-world"

NONE # "12345" (no alphabetic chars)Consecutive character sequences:

- consecutive_upper: Max run of uppercase (detects SHOUTING or constants)

- consecutive_lower: Max run of lowercase

- consecutive_digits: Max run of digits (detects IDs, timestamps)

Repetition metrics:

- max_repeat_run: Longest single-character repetition ("aaaaaa" → 6)

- repeat_ratio: Proportion of string in repetitive runs

- unique_char_ratio: Unique characters / total length

5.3 Structural Flags (Boolean Detectors)

Binary flags for common patterns:

- Base64

- Hex

- Camel case

- URL like

- UUID like

- ...

5.4 Lexical Metrics

Word-level analysis (when whitespace is present):

- word_count: Number of words

- avg_word_length: Mean word length

- max_word_length: Longest word

- capitalized_words: Count starting with uppercase

- uppercase_words: Count of ALL-CAPS words

6. Practical Scenarios

Here is how we combine these abstract metrics to solve real problems.

Scenario A: The "Needle in the Haystack" (Secret Detection)

Goal: Find an API key accidentally pasted into a chat log.

The Signature: API keys are designed to be unguessable. They are the "loudest" objects mathematically.

1. Shannon Entropy: > 4.5 (Very High)

2. Dictionary Words: 0 (No English words)

3. Whitespace: None.

Scenario B: Synthetic Data Validation

Goal: You generated 1,000 synthetic addresses for testing. Do they look real?

The Signature: Don't check the values; check the distribution.

1. Calculate the metric distribution of your real data (e.g., "Real addresses have an avg entropy of 3.2").

2. Compare it to your synthetic data.

3. If your synthetic data has an entropy of 1.5, your generator is likely just repeating the same few street names.

Scenario C: Anomaly Detection

Goal: Detect when a log file goes from "normal operations" to "system panic."

The Signature:

- Normal Log: "User logged in", "Job started". (Predictable, medium entropy).

- Panic Log: Stack traces, hex dumps, binary garbage. (Sudden spike in entropy and special characters).

- Alert: Trigger when the running average of entropy shifts by more than 2 standard deviations.

7. Conclusion

Quantitative text analysis is a reminder that we don't always need AI to solve data problems. By treating text as data points rather than sentences, we unlock a toolkit that is fast, explainable, and remarkably precise.

Key Takeaways:

- Entropy measures unpredictability. Use it to find secrets and anomalies.

- Compression measures redundancy. Use it to detect patterns and structure.

- Context is king. A number is only useful when compared against a baseline.

Next time you are faced with a massive dataset, before you reach for the latest Large Language Model, try calculating the entropy first. The math might just tell you everything you need to know.